If you have read any of my other blogs you’ll know I am trying to bring recent science around behaviour forward and into an app which uses these insights to help myself (and anyone else who wants to) get better at achieving the changes and goals I set my mind to.

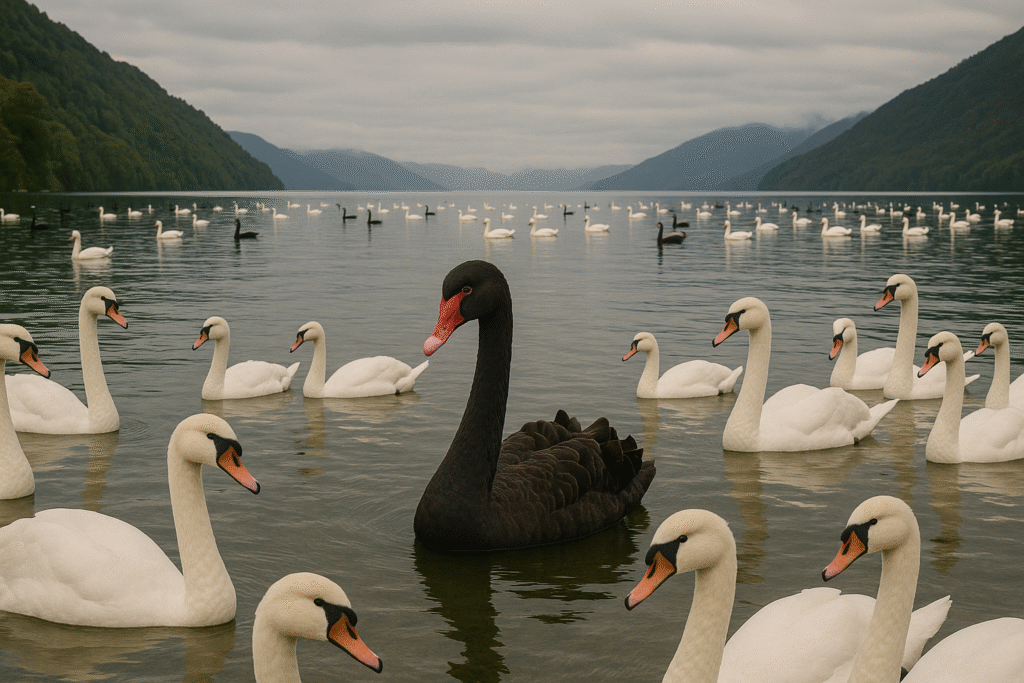

Exceptional events are like black swans surround by white – easy to overlook until they derail our plans. In this blog, I am looking at how we underestimate that outsized impact from things that we believe to be rare. As always, for clarity, when you spot text which is Dark Orange it is directly from the research papers, everything else is my fault. You can find full details of the research papers mentioned at the bottom of the post.

Why those one offs could be much worse for your progress than you anticipate.

On the journey to our goals, our progress is often planned, or at least hoped to be a fairly straight line. This would be easy if everything went to plan and ran like clock work. However, pesky unforeseen things crop up which halt our progress, if only a little bit… But how little of an impact do they really have? We tend to under estimate the frequency and impact of exceptional events, both during our planning, but also in the moment. Collectively these can have an outsized impact on achieving our goals.

Research from Abigail Sussman and Adam Alter in 2014 looked at the spending habits of individuals when looking at how frequently purchases were made and what impact that had on budgeting. They wanted to understand whether an exceptional event lead to a change in spending and budgeting.

Further research by Abigail and colleagues in 2021 investigated the consumption of foods which were enjoyed either frequently or infrequently. They hoped to understand if the research from 2014 carried over to eating decisions.

What specifically were the researchers trying to show?

In the first study, the researchers believed that consumers would under forecast the cost of exceptional expenses (such as birthday presents, a car repair or a new tv), but would be able to accurately forecast routine expenses. They also thought it likely that individuals would pay more for exceptional items if they occurred one at a time – do you think you’d spend less on birthday presents if your purchased them all at once for the entire year? Finally they wanted to show it is how we account and categorise these exceptional spends which leads to under budgeting and over spending.

In the second study they wanted to show that when people got the opportunity to eat food which was rarer, they would have larger portions, and that they would be less likely to reduce food intake following to compensate for over eating. The researchers believed this would occur because individuals would have the belief that these infrequent foods would have a smaller impact on one’s weight.

Collectively these two pieces of research are trying to improve the understanding around whether things which occur less frequently change how we think about them, and therefore how we react to them.

So were they right?

Looking at the finance study, Sussman and Alter showed that we are more willing to spend more for things we view as exceptional or one offs. Further they also demonstrated that part of the reason for this is how we categorise these one offs, as equally unique. They were able to show if we instead made them part of a larger category, we are more inclined to have more control on the spending.

For the diet study, it was shown when foods were eaten infrequently (once a month) the participants showed a preference for larger portions. The participants also believed that this would have a smaller impact on their weight. Fascinatingly in this study they found that on average, ~40% of foods eaten by a person would be considered infrequent foods for that person. Fortunately they managed to show in this study, that by informing people of this bias alone had an impact on portion size.

If we consider that 40% of the food we eat can be viewed as infrequent, and that when we view food as being rare, or infrequent we are more inclined to overindulge, it becomes clear how much this could impact a goal like controlling food intake. As it is the way we view the infrequent occurrence as being a one-off and therefore not needing to be accounted for, or being unlikely to have a negative impact on our progress, it is easy to see why just understanding this bias can begin to change our framing and how we approach exceptional events, or special treats.

We tend to think of these things… as though it’s a one off thing and so they don’t really have to matter that much. But in reality, they tend to add up over time.

Abigail Sussman

This research is important in understanding our ability to achieve goals, as while we may view these individual instances as rare and therefore unimportant; if we are to zoom back and notice the bigger trends, we are likely to notice that the thing we view as a one-off occurs more than we think at first glance. Like the individual black swan in the image, if we focus on the foreground we may assume it is insignificant, however if we take a closer look, there are many more. This higher occurrence and our tendency to view them as being of lower significance sets up infrequent moments to have a real and significant impact on our ability to achieve our goals.

So what can I do right now?

How will this look in Resolute?

Within the Resolute app you will find a few features which will help account for exceptional, infrequent and rare hiccups along the way to your goals.

- During goal setting Resolute will prompt you to look at incorporating a bigger buffer

- If you use the tracking features of resolute, you will be able categorise and report on how progress is going to help you identify earlier whether exceptional events might be impacting your progress

- While conducting progress reviews, Resolute will prompt the creation of plan of how to approach what to do when faced with an infrequent occurrence.

- Resolute will link to these blog posts, as the research shows being aware of this bias means you’re less likely to be impacted and behaviour in a way which is not aligned with your goals when faced with an exceptional event.

References

1. Sussman, A. B., Alter, A. L. (2012) The exception is the rule: Underestimating and overspending on exceptional expenses. Journal of Consumer Research. 39. 800-814. https://doi.org/10.1086/665833

2. Sussman, A. B., Paley, A., Alter, A. L. (2021) How and why our eating decisions neglect infrequently consumed foods. Journal of Consumer Research. 48. 2 251-269. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucab011